Ask A Bishop series “at” my alma mater, Ohio Wesleyan University, is giving me a chance to share what I have learned over the years from studying violence. Its goals are strikingly consistent.

Free and open to the public, so join me! Register here.

Speaker, Author, Cultural Critic

Ask A Bishop series “at” my alma mater, Ohio Wesleyan University, is giving me a chance to share what I have learned over the years from studying violence. Its goals are strikingly consistent.

Free and open to the public, so join me! Register here.

Imagine Otherwise is a great podcast I listen to regularly, so it is an honor to be a guest! And its host, Cathy Hannabach, founded Ideas on Fire, a remarkable company offering an array of editing services and professional development programming. I am pleased to have used their company for portions of From Slave Cabins to the White House.

In this interview, Cathy’s questions led me to share in some unexpected ways. I’m also happy to have had an opportunity to acknowledge the influence of Evie Shockley and Alicia Garza on my thinking. Listen and share widely! Full Episode

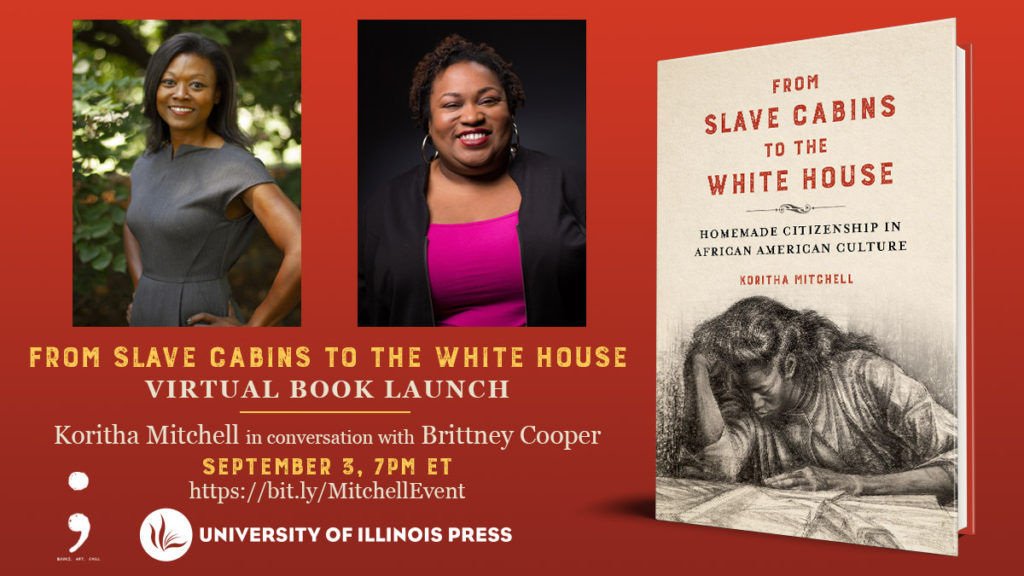

When I imagined the perfect book launch, this was my vision! I’ll be in conversation with Brittney Cooper, whose immeasurable contributions have inspired me for many years, and we are partnering with Semicolon, the Black woman-owned bookstore and art gallery in Chicago. I could not be happier about how From Slave Cabins to the White House will make its debut!

We will congregate via ZOOM on Thursday, September 3rd at 7pm Eastern time. It will be recorded and available later. To attend live and get all the updates, register at https://bit.ly/MitchellEvent

An official version of the letter below has been sent. Circulating a public version aligns with the mission of the Society of Senior Ford Fellows (SSFF). The organization takes a clear public stance oriented toward social justice, equity, and the advancement of intellectual rigor and democratic values in the United States and global society.

July 10, 2020

The Honorable Chad F. Wolf

Acting Secretary of Homeland Security

Office of the Executive Secretary

MS0525

Department of Homeland Security

2707 Martin Luther King Jr. Ave. SE

Washington, DC 20528-0525

Dear Acting Secretary Wolf:

The Society of Senior Ford Fellows (SSFF) would like to register its profound opposition to the Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s recent policy decision to revoke existing F-1 visas and deny applications for new F-1 visas to students who engage only in off-campus coursework during the coming year. The SSFF is a professional association formed by the more than 5000 prominent scholars in colleges, universities, and in the public and private sectors throughout the United States and globally who have received fellowships from the Ford Foundation.

This new policy is not consistent with widespread efforts by universities, colleges and other educational institutions to protect the health of students and staff in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic. Many of these efforts involve reducing on-campus activities as much as possible—particularly for vulnerable students, staff and educators—so that required physical distancing and other infection reduction practices can be implemented.

This new policy would be extremely damaging to the US educational systems and catastrophic for many international students and their families. This policy will put thousands of students in the horrible position of having to choose between meeting the requirement to participate in on-campus activities, and protecting their health, as well as that of their families and communities.

Even more problematic is that many educational institutions are planning for 100% distance learning in the coming year to protect public health. This includes the second largest four-year university system in the country, the California State University, with almost a half million students. Thousands of students in this system alone would lose eligibility to continue their education because of this new policy. It would also devastate the very foundation of these institutions, by depriving them of the intellectual, cultural, ideological and economic diversity that has propelled US educational institutions to excellence and made them aspirational worldwide.

This new policy for F-1 visa holders and applicants is unnecessary, disturbing and harmful. It would have extremely damaging effects on the student bodies of US educational institutions at all levels. It would compromise public health. Furthermore, it would severely damage the US economy and its international reputation.

We strongly urge you to reverse this policy immediately, before it further harms our critically important international student population, and the educational institutions that are the core of our nation’s society and economy.

Sincerely,

Society of Senior Ford Fellows

Susan C. Antón, President

February 26, 2020

Office of the President Harvard University

Massachusetts Hall

Cambridge, MA 02138 USA

Dear President Bacow and Board of Governors:

The Society of Senior Ford Fellows (SSFF) would like to make known our concern and disappointment over the decision to deny tenure to Dr. Lorgia García Peña. Dr. García Peña is a well-regarded member of our ranks, having been awarded Ford Dissertation and Postdoctoral Fellowships in 2006 and 2015, respectively, for her interdisciplinary work that examines the complexity and importance of Afro-Dominicanidad via musical, literary, political, and historical narratives. We also are deeply concerned about what Harvard’s action may imply about the university’s commitment to Ethnic Studies as a discipline and for scholars and students of color, to embracing new disciplines, fostering underrepresented professors and students, or enabling the development of innovative pedagogy. We are concerned that this matter may hamper Harvard’s ability to be fully engaged in efforts to change the academy for the better by making it truly reflective of current scholarship, demographics, or 21st century approaches to teaching. Given this unfortunate situation, we must join with various colleagues in the nation and abroad to ask that Harvard initiate a transparent and ethical release of information outlining the reasons for Dr. García Peña’s tenure denial.

Dr. García Peña’s scholarship has national and international acclaim. She has been awarded numerous accolades by important scholarly organizations for her publications and was named Harvard’s Professor of the Year in 2015. The following year she received the Roslyn Abramson Award for excellence in Undergraduate Teaching and Graduate Mentoring, and the Harvard Graduating Class of 2017 recognized her as Professor of Year. In addition to her distinction in research and teaching, Dr. García Peña has served on numerous search committees for tenure-track faculty positions and engaged in the hiring process for lecturers in various departments, as well as having been a principal member of the search committee for the 2019-2020 Warren Center Faculty Fellowships. This tenure decision is baffling, given her transformational work in American Studies, Ethnic Studies, and Latinx Studies, along with her prolific and high-quality record of publication and her status as a beloved teacher.

The SSFF considers Dr. García Peña a vital, important, and venerated member of our community. If the denial of tenure has not been entirely fair, as it appears, then this individual case would be tantamount to an affront against each one of us and puts us on guard. If an exceptional scholar like her can be denied tenure, then it seems that other scholars of color could meet the same fate at Harvard. We call on Harvard to rectify this situation and, in the process, restore our faith in your institution so that when we utter its motto, veritas, we know that indeed the word is made manifest there and in the academy as a whole.

Sincerely,

On Behalf of the Society of Senior Ford Fellows Board

Susan C. Antón, President

susan.anton@nyu.edu

I have never been shy about sharing that I don’t appreciate hearing the N-word in my workplace, which includes classrooms and conferences in which texts that liberally use the word will be examined. Besides writing an essay that touches on the issue (2012, details below), I have addressed this by presenting on a “syllabus roundtable” for SSAWW, the Society for the Study of American Women Writers (2015) and by presenting at an Ohio State University English department event about Teaching Tough Topics (2014). For that occasion, I titled my remarks: “The N-word: A Not-So-Tough Topic in the Classroom.”

Below, you’ll find my “Class Covenant,” which is typically on the last page of the course policies for every class I teach, especially those that don’t focus on authors in dominant identity categories. Please feel free to adopt or adapt to suit your purposes. I’m happy to help as many people as possible with effective tools. A gesture like *Adopted/Adapted from Koritha Mitchell would be appreciated. Below the covenant, you’ll find additional explanations and resources.

CLASS COVENANT

Dr. Koritha Mitchell

To ensure that our time together is enriching, students will abide by the terms of this agreement. Anyone in our intellectual community can suggest an addition; the group will decide to accept, reject, or revise it.

1) The majority of our thinking about the literature will be done outside of class. An hour and twenty minutes is not enough time to appreciate the richness of this material. Remaining enrolled in this course means that you are ready to devote the time, effort, and energy to reading and thinking about this literature that it deserves.

2) In this course, we are studying literature. Although we are committed to considering these texts within their historical contexts, we must remain aware that they are creative works and are therefore CRAFTED. We will look at not only the message but also the craft—the artistic elements—that shape the delivery of that message.

3) This class will be free of hate speech regarding sexual orientation, gender expression, race, and socio-economic status or background. Inflammatory remarks will not go unchecked and will not be tolerated. Each member of this class is responsible for fostering an environment in which people and their ideas are respected. For the same reasons, students will strive to make remarks that are informed by our material and the history that surrounds it.

4) The N-word won’t be used in this class by a person of any race, even if it consistently appears in our texts. The same goes for the “F” word, regardless of a person’s (perceived) sexual orientation or gender expression. And, this is simply not a space in which we call people “trash.”

5) Profanity will not be common currency in this class.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The N-word is not uttered in my classes, even if it appears in the reading. We simply say N or N’s when reading passages aloud. It easily becomes part of how we do things. It doesn’t take a PhD for my students to understand that we are literary critics, not re-enactors, so we need not let the text dictate what we give life to in the classroom. Just as their papers won’t generally refer to African Americans as “Negroes,” why must we operate as if the text leaves us no choice but to enact discursive violence? Is anything taken away because the word isn’t uttered while everyone is looking at it? Has learning been compromised? Might learning actually be enhanced because students aren’t having to work around the gut-punch some of them feel when they hear that word? The following help explain why I have adopted this practice:

UPDATE: as of March 4, 2019, The N-word in the Classroom: Just Say NO is available. It’s a 45-minute audio recording about how to handle racial and other slurs responsibly and with intellectual rigor. C19 Podcast: Official Publication of the Society for Nineteenth-Century Americanists. http://bit.ly/2TAkuU5

“Belief and Performance, Morrison and Me.” The Clearing, 1970-2010: Forty Years with Toni Morrison. Ed. Carmen Gillespie. Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell UP, 2012. 245 – 261. [downloadable from the Intellectual Autobiography section of http://www.korithamitchell.com/books-articles/]

“I’m a professor. My colleagues who let their students dictate what they teach are cowards.” Vox. June 10, 2015.

Also see: “An Open Letter to White People From Two Professors of Color: Step Up!” (co-authored with anthropologist Alex E. Chávez). The Huffington Post. March 21, 2017.

Also see: “In America, White Women Can Get Away With Almost Anything.” The Huffington Post. March 16, 2018.

Connected to all these issues: “Responsible Teaching in a Violent Culture” http://www.korithamitchell.com/workshops/

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825-1911) was one of the most important black woman activist-authors of the nineteenth century—easily as prominent as Frederick Douglass. When many rejected the notion that African Americans should be anything other than slaves and opposed the idea of women speaking in public, Watkins Harper was an antislavery lecturer appreciated by significant crowds and by colleagues such as Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, William Still, Susan B. Anthony, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. In the first six weeks of the fall of 1854, she traveled to 20 cities and gave at least 31 lectures. That same year, she published Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects, which sold more than 10,000 copies, was enlarged and reissued within 3 years, and enjoyed at least 20 reprintings in her lifetime. After having written three serialized novels, she released her most famous novel, Iola Leroy, when she was 67 years old, and it was reprinted four times in four years. How could such a powerful orator and prolific writer fade from American memory?

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825-1911) was one of the most important black woman activist-authors of the nineteenth century—easily as prominent as Frederick Douglass. When many rejected the notion that African Americans should be anything other than slaves and opposed the idea of women speaking in public, Watkins Harper was an antislavery lecturer appreciated by significant crowds and by colleagues such as Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, William Still, Susan B. Anthony, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. In the first six weeks of the fall of 1854, she traveled to 20 cities and gave at least 31 lectures. That same year, she published Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects, which sold more than 10,000 copies, was enlarged and reissued within 3 years, and enjoyed at least 20 reprintings in her lifetime. After having written three serialized novels, she released her most famous novel, Iola Leroy, when she was 67 years old, and it was reprinted four times in four years. How could such a powerful orator and prolific writer fade from American memory?

It certainly is not because she did not work hard or failed to command respect from those exposed to her work. As a Unitarian who was also quite active in the AME church, she felt a tremendous duty to steer the United States toward greater justice. When her demanding travel schedule tested the limits of her health, she admitted to friends in letters how difficult it was, but she persisted! Meanwhile, she also seemed to anticipate the possible erasure of her labor as well as its likely causes. In an 1866 speech, she shared that, as soon as her husband died, authorities “swept the very milk-crocks and wash tubs from my hands,” depriving her of the means to support her children. She ended this story with, “I say, then, that justice is not fulfilled so long as woman is unequal before the law” (311). Thus, Harper understood that women could be denied the resources needed to work.

As important, Harper understood that even when women created a work life despite meager resources, the politics of recognition unjustly obscured their contributions. In an 1878 article titled “Colored Women of America,” she was unequivocal: “The women as a class are quite equal to the men in energy and executive ability. In fact I find by close observation, that the mothers are the levers which move in education. The men talk about it, especially about election time, if they want an office for self or their candidate, but the women work most for it” (315).

Harper’s public career was most active from the 1850s to the 1890s, an impressive 50 years. She was at the forefront of movements for abolition, public education, temperance, and voting rights. And she did this work through leadership positions within black women’s organizations, such as the National Association of Colored Women (NACW). At the same time, she was one of the most prominent black women in predominantly white organizations, such as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU)—despite the racism she faced.

In short, Harper’s life and work exemplify the tradition among black women to engage in justice-oriented activism not only while encountering hostility but also whether or not they receive the recognition that seem to flow to their black male and white woman colleagues.

Besides having spoken plainly about black women’s labor in speeches and essays, Harper made the pursuit of meaningful work a major theme in Iola Leroy so that her protagonist’s journey Is not dominated by the marriage proposals she received. Harper’s novel therefore imagined more space not only for black women’s labor but also for its recognition. Frances E. W. Harper understood the forces that might conspire to diminish her contributions, and she left evidence that she did not simply capitulate to those (admittedly quite powerful and enduring) forces.

The new Broadview edition of Iola Leroy honors this aspect of its author’s legacy… and so much more. For more details, please visit https://broadviewpress.com/product/iola-leroy/#tab-description

When 5 police officers were killed in Dallas, it was so easy for Americans to go back to ignoring the brutality routinely visited on Black and Brown communities. That easy shift made me even more determined to say what I say here. We must do better! And that “we” needs to include white people to a degree that it rarely does.

Full text of audio:

My name is Koritha Mitchell. I’ve been surrounded by whites my whole life and that has not translated into being surrounded by excellence. In fact, the older I get and the more I achieve, the more I see how much American culture lies to create the assumption that whiteness brings excellence. The truth is that our country’s standards for white people are so low that most of our problems—including the unrelenting violence against people of color—can be traced to those low standards.

It doesn’t take much at all for a white person to be considered good. As long as they avoid killing someone themselves, no one is going to demand anything else of them. Whites don’t need to do anything decent for anyone, especially not people outside of their own family, and yet, everyone will assume that they are good people. Even when whites do undeniably harmful things, American culture explains it away. This is why our society subjects impressive people of color to dehumanization that a white person who behaves despicably doesn’t encounter. You know, like when Dylan Roof killed 9 black people in their church and the police gave him a bulletproof vest and bought him lunch. As Dr. David Leonard puts it so well, American institutions literally manufacture innocence for whites.

Whites are considered good pretty much without any reference to actual standards. If Americans used standards, like does this person contribute to society, to the common good, then we’d have to admit that many white people don’t measure up and don’t even try to measure up because they are not expected to. White people are considered to be good based on their demographic, not based on any actual criteria. This is more of a social problem than a personal one; it’s about American society’s low expectations and how those low expectations shape behavior. The culture is set up to ensure that whites are mediocre (or worse) and that non-white people suffer because of the low standards to which white people are held.

Again, this is not personal; this is cultural and systemic, so whites can refuse to live according to the low expectations their country has of them. Will they? That’s a question whose relevance will not fade as I watch the dehumanization, demonization, and murder of Black and Brown people on repeat.

Because our society has exceedingly low expectations of whites, we have a society full of people who feel no responsibility for doing anything that benefits anyone but themselves. At the same time, many will do anything or go along with anything that hurts other people if they believe it will bring more opportunities and resources to the few people in their family that they care about. And that’s exactly what this country encourages, going through the world with an attitude of “I’ve got mine; I don’t give a damn if you ever get a chance to get yours.” This is why the United States is full of cities where some neighborhoods have high schools that look like college campuses while high schools down the street look and feel like prisons. White Americans are constantly taught that it’s only right for them to move through the world focused only on their own opportunities and resources. Because that’s the American Way, I have to tell you: My name is Koritha Mitchell. I’ve been surrounded by whites my whole life. That has meant being surrounded by examples of white mediocrity. It has also meant routinely being a witness as innocence is manufactured for whites who don’t even have the decency to be mediocre.

And I want to be clear: white mediocrity is very much linked to violence against people of color. Whiteness is a powerful set of beliefs that yield material outcomes. Whiteness determines who has wealth in this country, who can expect to get justice, who constantly gets the benefit of the doubt. Whiteness (and the racism it facilitates) are not personal. That’s why a white man or woman doesn’t have to do anything particularly well to end up with above-average success. Whites prove to be mediocre (or worse) all the time but they are constantly given chances to succeed, whether they deserve it or not. And this is to say nothing about how federal programs like FHA loans were funneled away from people of color and toward whites so that white families could build wealth while others were barred from doing so. Therefore, a white family doesn’t have to contain particularly hard-working people to have 4X the wealth of a black family that is full of generations of people who worked hard.

Still, as I watch the death toll of Black and Brown folk killed by people like George Zimmerman, Dylan Roof, and by police, I can’t help but notice how much injustice is fueled by this country’s exceedingly low expectations of white people and by how this country encourages white people to have exceedingly low expectations of themselves. There are too many examples to name, so I’ll give a few and ask that you fill in others for yourself.

American expectations of whites are so low that they are never assumed capable of identifying with anyone but themselves. If you’re going to finally make a movie that doesn’t cast Muslims as terrorists—the film about the famous scholar and poet Rumi, for example—then naturally, you have to cast a white actor to play Rumi. You can’t expect whites to support something if they aren’t the center of it. Or, if you’re going to tell a story about working class students struggling in schools that our society refuses to invest in, you have to cast a white savior. Why honor the black and brown men and women who kept those communities afloat with no resources? Whites aren’t interested in that. You can’t have a compelling story if whites don’t dominate it. Of course, the same goes for books, but I’m not just talking about how no one expects white readers to identify with characters who aren’t white. [Sidebar: Low expectations are why writers of color get such meager opportunities while mediocre white writers benefit from extraordinary marketing. That pitiful novel The Help, which became not only a bestseller but also a blockbuster film, immediately comes to mind.] But, as I say, I’m not just thinking of novels; I’m thinking of our nation’s textbooks. White people have such low expectations of themselves to make life better for anyone but themselves that even our textbooks are constantly whitewashed; powerful Americans erase anything that acknowledges that whites are in power, not because they deserve to be but because everything is set up to make sure they win, whether they deserve to or not.

We know that this is a racist country, that if history is taught the way it has always been taught, then white students will have role models and a sense of pride… and students of color won’t, but do we truly change anything about American education? No! Heaven forbid that white teachers would have to do better. Heaven forbid that they’d have to keep growing and learning. Heaven forbid that they be held accountable when whites are the only students that typically blossom under their guidance.

We know that this is a heterosexist country, that if schooling continues as it always has, then straight-identified students will have role models and a sense of pride… and LGBTQ+ students won’t, but do we truly change American education? No! Heaven forbid that straight teachers would have to do better. Surely, we can’t expect them to keep growing and learning. We can’t expect to assess them negatively when straight students are the only ones who thrive under their tutelage.

Given these American tendencies, when you have black and brown people dying in the streets, whites aren’t encouraged to assess themselves or each other with actual standards. Just being white means they are good people. They didn’t go out and shoot Tamir Rice or kill Sandra Bland or Philando Castile or Alton Sterling or Pedro Villanueva or Anthony Nunez. They didn’t go out and lynch someone in Piedmont Park and harass Kai Kitchen, so “it’s a shame what’s happening, but it has nothing to do with me,” they reason. But how could that be true? After all, these American tragedies happen because our entire culture makes it not only possible but also common. And a society that expects nothing of white people is dangerous because whites who do nothing reinforce the status quo; they keep our systems working the way they do. And make no mistake, when American institutions work the way they were designed to work, they ensure that black and brown excellence will mean little because white mediocrity will be considered merit. (Joe Walsh’s tweet to Obama is a good example.) Furthermore, when American institutions work as designed, they ensure that even when whites do actual harm—when they don’t have the decency to be mediocre—innocence will be manufactured them.

I say this because I’m clear about something that this culture wants to prevent everyone from understanding: black and brown people are not under attack because they’ve done something wrong. These injustices continue, but that’s not because black and brown activists haven’t used the right strategy. People love to claim, you have to be calm as you protest, you have to speak in a way that the powerful will respect, you have to dress in a way that doesn’t alienate people. But following such rules does not matter. There’s no right way to protest your own dehumanization and your community’s destruction, especially when your country insists that there’s nothing violent, uncivilized, and un-American about how it routinely dehumanizes and destroys certain populations. If there were a right way to protest, the brutality would’ve ended long ago because black and brown people have tried literally every strategy, whether it’s accommodation and assimilation or separatism. Nothing has kept us safe. Why? Because these problems are not caused by OUR choices. The murderous conditions under which we live are not of our own making; they white-authored. Whites insisted that the practices supporting whiteness would not just support whiteness but also do everything imaginable to rob everyone else of life chances. Even the most middle-of-the-road white person benefits from the whiteness that keeps them draped in opportunity and resources while others are stripped of opportunity and resources, so it’s time to get real: Do you actually care about fair play? Do you really believe that fair play is the American way? Then you must begin judging whites based on actual standards, not just demographics. Being white shouldn’t be enough to be considered good. Low expectations for white people. That’s what’s killing us. Please, do better.

It took almost all weekend, but I finally finished the revisions of Chapter 5 of my book-in-progress. I’ve been working on these revisions in the midst of teaching and committee work, so I could only take baby steps. Every day, I worked to find 30 minutes or whatever I could, literally whenever I could. It’s amazing how far baby steps can take you!

My fabulous friend Carie gave me one of the sweatshirts I’ve been coveting, so I had an extra dose of Baldwin helping me tame Ch 5!

We often hear people talk about “needing” large, uninterrupted blocks of time to make progress on a project. But, as Kerry Ann Rockquemore and her NCFDD team make clear, that’s a myth. Besides, the profession simply isn’t structured so that I can count on having uninterrupted blocks of time. So, I’d rather make decisions with that reality in mind.

Throughout my revision process, I’ve been declaring #running helps #writing! It took me 7 weeks to revise chapter 5 in the midst of all my other obligations, and I’m convinced that running regularly helped that process. Well, many friends have recently shared the latest study to prove that my hunch was right: “Which Type of Exercise Is Best for the Brain?” I hope you’ll read it and be inspired to continue your running or walking regimen…or begin one. (Remember, I’ve got tips on beginning here.)

Unfortunately, it’s getting to the point that I run only 2 times per week. So, as teaching and committee obligations have put pressure on my writing goals, I have been borrowing time and energy from my running bank. I don’t want to keep doing that, but I’m also trying to remember the value of baby steps. The fact that I’ve created accountability for those 2 days per week means that I’m getting in 2 days rather than none. That counts! I’ll keep taking those baby steps, knowing that they add up. Capital City Half Marathon, I’m still coming for you!

This weekend, I completely checked out of my life of responsibility and checked in with myself. I made my first trip to Portland, Oregon, to run the Oregon Winter Half Marathon. The race was Saturday morning at the Reserve Vineyard and Golf Club. It was an intimate race and a perfect trip!

I made these plans months ago, long before I could have anticipated how much I would need it. When I would have been giving my Fall semester finals, I traveled for a family funeral. Within 10 days, I was submitting grades and helping to host Christmas dinner. The week after that was a trip as a university representative. The week after that was the annual convention of the Modern Language Association (MLA), from which I returned on Sunday and began teaching on Tuesday. In the midst of all this travel, of course, were letters of recommendation, etc., etc., etc. By the Wednesday before I left for Portland, I had to admit that some kind of rebellion was underway. I had somehow neglected to put TWO meetings in my calendar! I still made it to the meetings, but…

I’ve had some great experiences by combining running with professional presentations. For example, in December 2011, I gave a lecture at Columbia University on a Friday, flew across the country on Saturday, and ran a half marathon on the Las Vegas Strip on Sunday. Similarly, in March 2014, I gave a lecture at the Library of Congress on Friday afternoon and ran a half marathon through the nation’s capitol on Saturday morning. I’ve managed to duplicate those sorts of experiences several other times, and I found it exhilarating. But this trip taught me that it can be rejuvenating to check out of my normal life and simply be present to all that running gives me.

I arrived early Friday and got to hang out with a friend who took me to the famous Powell’s Bookstore and a few other spots. Then, I had the rest of the day to lounge around my cute hotel room. The race was the next morning but not until 8am, so it wasn’t a ridiculously early morning. Also, I chose a hotel that was a quick, easy drive to the race site. So, after hanging out a bit with fellow runners, I was back in my room by noon and had the rest of the day to lounge around, polish my nails, watch bad TV, write in my journal, and just be in the moment and count blessings!

Alright, some actual race details: Portland got record amounts of rain in December and early January, so there were unavoidable puddles almost immediately. Trying to avoid them by running on the grass only got you into mud, which is even heavier, so my shoes were soaked. It felt like I was running with weights on my feet, but with temperatures in the 40s, being wet didn’t translate into being cold. It rained for about half the time we were out, and I dressed perfectly for the conditions. After the race, we were served piping hot soup with great pretzel rolls! The medal doubles as a belt buckle, and they even put our names on it! I took is slow and easy, finishing in 2:24:23 or about 11 minutes per mile, and I met my goal of running the entire time.

Alright, some actual race details: Portland got record amounts of rain in December and early January, so there were unavoidable puddles almost immediately. Trying to avoid them by running on the grass only got you into mud, which is even heavier, so my shoes were soaked. It felt like I was running with weights on my feet, but with temperatures in the 40s, being wet didn’t translate into being cold. It rained for about half the time we were out, and I dressed perfectly for the conditions. After the race, we were served piping hot soup with great pretzel rolls! The medal doubles as a belt buckle, and they even put our names on it! I took is slow and easy, finishing in 2:24:23 or about 11 minutes per mile, and I met my goal of running the entire time.

Ultimately, this weekend was a time for checking in with myself. I looked at all that I managed to do between September and early January and was pleased to see that, for all I did for others and for other people’s agendas, I never lost sight of my own. So, I made steady progress on my book manuscript and ran very consistently for 8 of the 10 weeks I was officially training for this race. I also never got sick, praise the Lord! So, I was beginning to feel out of sorts, and this weekend allowed me to see that it was the beginning of some kind of slip, but nothing had gotten truly lost. I’m now regrouping, but I’m doing so before having lost my way. (Another blessing to count!)

For the past few years, my goals have been about how I want to feel. I want to feel like I’m doing important work, but I don’t want to feel awful (or vaguely miserable) while doing that work. As I often say, I’ll never get in your way if you’re working for a halo or a cape. I’m not trying to be anybody’s saint or superhero. Increasingly, I believe that success isn’t success unless I feel healthy and happy. Checking out so that I could check in with myself reassured me that those priorities are still intact.